The “Inaudible prayers” should be read out loud

Originally posted on Feb 10, 2020.

We believe that the so-called “inaudible” prayers should be read out loud, to the hearing of the faithful, so that the people of God may participate more fully in the celebration of the Divine Mysteries. We have addressed this subject in our book, The Heavenly Banquet,1 and we draw this post from it, with some editing.

The subject of the liturgical prayers read by the celebrant — whether he should read them inaudibly or to the hearing of the faithful — has been hotly debated in recent years, particularly in Greece and Cyprus, but also here in America. Among the voices raised in favor of reading the prayers out loud are those of St. Tikhon of Moscow and St. John of Kronstadt. The latter is quoted to have said, “The priest or the bishop recites many prayers to himself; it would be much more interesting and profitable for the minds and hearts of Christians to be aware of the full text of the Liturgy.”

One of the key points we have made throughout The Heavenly Banquet is that the prayers the priest reads softly to himself should be heard by all the people. The prevalent practice of reading such prayers “inaudibly” does not make sense for two reasons:

First, because the people hear only the conclusion of a prayer, introduced by a conjunction (“for” or “so that”), to which they have to respond with their Amen, without having heard what the prayer is about; second, because such prayers divide the Ecclesia between clergy and people, the latter deemed not worthy to hear the supposedly “secret” and “arcane” prayers. Bishop Hilarion Alfeyev calls the offering of the prayers silently a “barrier between the priest and his flock.”2

The early Church did not pray silently. Why should the priest pray silently when the Lord instituted the Holy Eucharist loudly and directed His disciples to do what He did? There is unequivocal testimony that the Church since the beginning did what her Founder did, as well as the way He did it. The Apostle Paul (writing about A.D. 50) presupposes that the prayers offered were said loudly: “If you offer your blessing with the spirit, how can any one in the position of an outsider say the ‘Amen’ to your thanksgiving when he does not know what you are saying? For you may give thanks well enough, but the other man is not edified” (1 Cor. 14:16-17).

In the Didachē or The Teaching of the Apostles (ca. A.D. 90-110) we have the earliest mention of a rudimentary Anaphora prayer, and of the thanksgiving that follows offered by the people.

St. Justin the Martyr (ca. A.D. 165) says that the celebrant

“sends up praise and glory to the Father of the universe through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit and offers thanksgiving at some length that we have been deemed worthy to receive these things from him. When he has finished the prayers and the thanksgivings, the whole congregation present assents, saying, ‘Amen.’ ‘Amen’ in the Hebrew language meaning, ‘So be it.’” 3

Clearly the prayer was offered to the hearing of the people.

One hundred years later St. Dionysius of Alexandria († A.D. 264 or 265) offers us an even stronger testimony, saying that the people “listened to the Eucharistic prayers and joined in the Amen.”4

The Council of Laodicea (A.D. 364) prescribed that “after the Catechumens and the Penitents are dismissed, three prayers for the faithful shall be said, the first silently and the other two be said viva voce.” Today, the first of these prayers is eliminated, while the other two whenever they are said are said silently.

The Constitutions of the Holy Apostles (written ca. A.D. 380) has the hierarch say a very long Anaphora out loud, at the end of which it says, “And let all the people say, Amen.” 5 So much so was the Great Anaphora Prayer of Thanksgiving said aloud, that bishops were elected depending upon their ability to offer extemporaneously a beautifully crafted prayer! The West early on settled with only one Anaphora Prayer, which became known as the Canon. Eventually the Orthodox Church in the East adapted first the Anaphora Prayer of St. Basil the Great, and later one settled with the shorter Anaphora Prayer of St. John Chrysostom.

St. John Chrysostom († Sept. 14, 407), after whom the Divine Liturgy is named, “gives us tangible proof that in his time the Liturgy continued to preserve its earlier, completely open character and the audible reading of the Eucharistic prayers was the norm”:

“In the most awful mysteries themselves, the priest prays for the people and the people also pray for the priest; for the words, ‘with thy spirit,’ are nothing else than this. The offering of thanksgiving again is common: for neither does he give thanks alone, but also all the people.’”

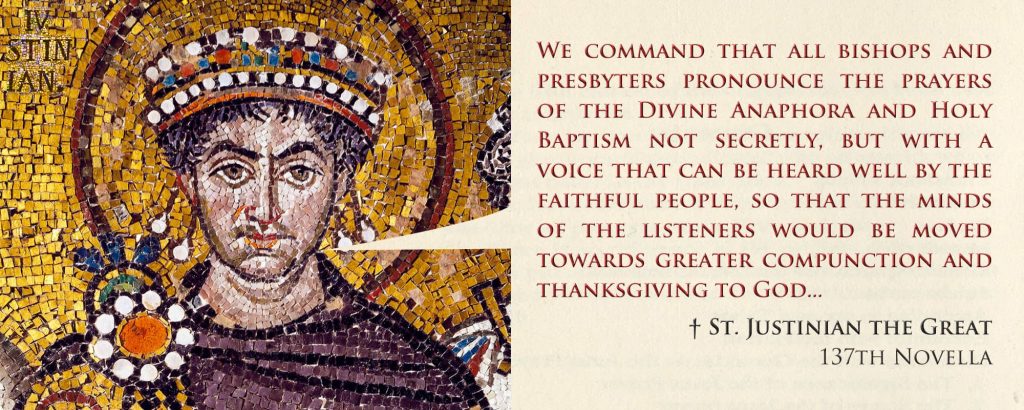

St. Justinian the Great in his 137th Novella (issued March 26, 565) protested vigorously and forbade the practice that had crept in, to recite the priestly prayers silently. Struggling in vain against this innovation, and referring to Romans and I Corinthians 14, he decreed:

We command that all bishops and presbyters pronounce the prayers of the Divine Anaphora and Holy Baptism not secretly, but with a voice that can be heard well by the faithful people, so that the minds of the listeners would be moved towards greater compunction and thanksgiving to God. It is fitting that prayers to our Lord Jesus Christ our God, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, in all occasions and at other services be pronounced loudly [meta fōnēs]. Those refusing to do so will give their answer before God’s throne and if we should find out, we will not leave them without punishment. 6

A liturgist notes the following: “Justinian was concerned to stamp out an innovation which he rightly considered harmful to liturgical devotion. He was unsuccessful, and his failure opened the way to a fundamental change not only in liturgical practice but in popular Eucharistic piety.” 7

Indeed, this practice is “harmful to liturgical devotion” and the defense of its continued practice, other than “it is tradition,” is untenable. However, “by the 8th century the secret reading of the Anaphora becomes the commonly accepted practice.” This is inferred from an incident recounted by John Moschos (beg. 7th C.), who attests that “because the presbyters in certain places recited the Anaphora Prayer out loud the children learned it by heart.” However, he must have been critical of this practice, because he attributed their being struck by lightning to their repeating the Anaphora Prayer.

Possible reasons reading inaudibly became prevalent

Various opinions have been advanced for the reasons that gave rise to this significant change. A. Golubstsov listed a few reasons why the prayers ceased to be read publicly:

- In an effort to reduce the growing length of the liturgy, the prayers were read silently by the priest as the deacon was intoning the petitions.

- The secret reading became incorporated into the disciplina arcana (‘secret discipline’) whereby it was felt that those who were ‘uninitiated’ were unable to hear about the mysteries of the faith or of worship. This encouraged the previously mentioned division between the clergy and laity.

- It was closely related to the period when the practice of frequent communion ceased. (This last point is not a reason, but it attributes the change to a general weakening of the faith.)

The late Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens († 2008) gave his reasons for the change from loud to “secret” “either because [the priest] had a weak voice, or because his voice was not heard well on account of the distance and the lack of loudspeakers.” He was in favor of bringing back the ancient practice of the loud reading of most prayers, especially of the two great prayers of the Holy Anaphora. Fr. Alkiviadis Calivas opines that, “It was introduced probably out of deep reverence for God.” He also reports that “The Ecumenical Patriarchate... has recommended and has urged its clergy to read the prayers of the Divine Liturgy and especially the Anaphora aloud.” This is encouraging, except that this “recommendation,” to my knowledge, has not been communicated to the clergy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

That the holy Anaphora prayer was too sacred to be heard by profane ears is not a plausible explanation. After all, the words of the Institution are said aloud! Other prayers not so arcane (such as those in the first part of the Divine Liturgy) are also said “inaudibly.” Today, with the current education of both clergy and people, and the use of sound equipment, there is no justification for retaining a practice that arose out of circumstances that no longer exist.

Opponents to the practice of reading the prayers out loud argue that the long-standing practice of reciting the prayers “secretly” gives certain legitimacy to the practice. “How could such practice be carried on for some 1,400 years unless it was the work of the Holy Spirit?” they say. We could reply that the same thing happened with the frequency (read infrequency) of the reception of Holy Communion. But we are not going to. Long practice alone is not enough. There needs to be a good justification, and there isn’t any for today’s reality.

Another argument advanced is that the wide attendance of the Divine Liturgy by non-Orthodox and even non-Christians precludes these prayers from being divulged. It is felt that the mysterium arcanum is not preserved. Which precisely are the words that must be kept secret? Today everything is in print. What we shout over the rooftops shall we whisper in our house of prayer? Besides, the Canons of the Church are trampled upon when we allow non-Orthodox, even non-Christians, to be present during the Divine Liturgy – in places of honor at that! – when according to the holy Canons not even Catechumens are allowed to be present in the “Liturgy of the faithful”!

Still others will say that the secretive recitation creates an atmosphere of mystery conducive to prayer for clergy and people alike. They are not called mysteries because they are supposed to be kept concealed and secret, nor because they create an atmosphere of mystique and mysteriousness. Our mysteries are not cabala, magic incantations and hocus-pocus. They are mysteries because they are sublime, incomprehensible and unfathomable, and they give life to those who approach them with faith.

The current practice of chanting (or singing by a mixed choir, introduced in America and elsewhere) to “cover” the time it takes the priest to recite the prayers to himself, seriously harms the full participation of the people in the Liturgy, and shifts their focus of attention from what is taking place to an atmosphere of a recital. Also, by removing these prayers from the ears of the faithful, the service becomes unintelligible to them.

The current usage of reciting sotto voce the Great Anaphora Prayer of Thanksgiving, the most important prayer of the entire Liturgy, is unacceptable, even offensive to the people. Especially the Anaphora contained in the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, celebrated on the Sundays of Great Lent, is a superb synopsis of the core of our worship, which should be read aloud and slowly despite its length. How can this prayer remain secret and hidden from the faithful? It should be read in its entirety, even if we would have to curtail the sermon!2

This is a sermon the faithful should memorize – as the children did in earlier times – before the iPhone, Facebook, Twitter and Internet were invented. We plea for its reading out loud, for the edification of the holy people of God. They deserve it. They are entitled to it. We are glad that it has been introduced in many metropolises in Greece and in Cyprus, as it is in many parishes in the United States.

We conclude by emphasizing that Liturgy is not a spectacle, a theatrical play, a concert, where we go to see and hear something staged. As the word liturgy says, it is the work of the people, so all the faithful gathered are expected to be active participants not passive spectators of the sacred Mysteries celebrated. The people of God must take charge of their parts, their replies, their hymns, and their prayers.

“The people standing in the church are not passive attendees, but are co-celebrants with the officiating priest or bishop, and they must be able to follow the course of the Liturgy and participate in the prayers. Only in this way can the Liturgy be real liturgy–common worship–and the Church an ecclesia—the people of God assembled for the Eucharist.” (+ Archbishop Paul of Finland)

APPENDIX

We bring four rather extensive readings to emphasize the importance of the liturgical prayers and the need to read them aloud. The first is from St. John Chrysostom’s Sermon 18 of Second Corinthians:

But there are occasions in which there is no difference at all between the priest and those under him; for instance, when we are to partake of the awful mysteries; for we are all alike counted worthy of the same things: not as under the Old Testament [when] the priest ate some things and those under him others, and it was not lawful for the people to partake of those things whereof the priest partook. But not so now, but before all one body is set and one cup. And in the prayers also, one may observe the people contributing much. For in behalf of the possessed, in behalf of those under penance, the prayers are made in common both by the priest and by them; and all say one prayer, the prayer replete with pity. Again when we exclude from the holy precincts those who are unable to partake of the holy table, it behooves that another prayer be offered, and we all alike fall upon the ground, and all alike rise up. Again, in the most awful mysteries themselves, the priest prays for the people and the people also pray for the priest; for the words, “with thy spirit,” are nothing else than this. The offering of thanksgiving again is common: for neither does he give thanks alone, but also all the people. For having first taken their voices, next when they assent that it is “meet and right so to do,” then he begins the thanksgiving. And why marvellest thou that the people any where utter aught with the priest, when indeed even with the very Cherubim, and the powers above, they send up in common those sacred hymns? Now I have said all this in order that each one of the laity also may be wary, that we may understand that we are all one body, having such difference amongst ourselves as members with members; and may not throw the whole upon the priests but ourselves also so care for the whole church as for a body common to us.

The second quote is from Archbishop Paul of Finland:

How can the whole assembly of God’s people participate in the sacrament of redemption with full understanding and true feeling and realize that they are a royal priesthood bringing spiritual offerings, if they hear only fragments or closing sentences of the common prayers without being aware of their meaning as a whole? As this is still most often the case, the people present can only follow the service without any other support than their own personal mood of prayer or else remain a more or less distracted audience. In the latter case people tend to pay special attention to the outward, aesthetical side of the Liturgy, and indulge in admiring the splendour of the service and the fine singing. It is true that these aspects, reflecting the heavenly glory of God, have their own value, but only as a framework for the content of the Eucharist. They must not become ends in themselves. The early Church lacked any outward splendour; Eucharistic solemnity was found in the joyous encounter with the Risen Christ.” (The Faith We Hold, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, N.Y. 1980, pp. 48-49.)

The third testimony comes through the penetrating and illumined words of Fr. George Mastrantonis of blessed memory:

The inaudible prayers are approximately one half of the Divine Liturgy ... The prayers embody the substance of the Divine Liturgy... The spoken words, taken without a knowledge of the inaudible prayers in reference to the Mysterion of the Holy Eucharist, are incomplete ... In the early Church, prayers for the sanctification of the Holy Gifts were freely selected or composed expressing the same meaning and belief in the Mysterion of the “change” of the blessed Species, Bread and Wine, into the Very Body and the very Blood of Jesus Christ. At that time, the whole Liturgy was read and chanted aloud by the priest (Proestos) and the people. Even later, at the time of St. Chrysostom, the prayers were read aloud. Later still, because of the emphasis of mysticism and for other reasons, the prayers, which in themselves contain the heart of the Mysterion, were designated to be read inaudibly by the priest within the enclosure of the sanctuary. The grandeur and meaningful depth of the inaudible prayers of the Holy Eucharist, which are not heard by the people, is a loss and privation of the faithful. This is especially true of that part of the long Prayer of Sanctification, the Epiclēsis, which is at the very moment of the sanctification of the Holy Gifts, but no longer read audibly, although its content includes the faithful. The faithful are urged to read the inaudible prayers with reverence and thoughtfulness in order to participate more fully in the Divine Eucharist.” (The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom of the Eastern Orthodox Church, O Logos Mission, St. Louis, Missouri 19662, p. 62.)

The fourth and final quote is from Fr. Alexander Schmemann, addressing primarily to the Great Anaphora Prayer of Thanksgiving:

Already for several centuries now, the laity, the people of God, whom the apostle Peter called “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people” (1 Pt. 2:9), have simply not heard and thus do not know this veritable prayer of prayers, through which the mystery is completed and the essence and calling of the Church herself are fulfilled. All the faithful hear are individual exclamations and fragmented phrases, whose [sic] interconnection — and sometimes even simple meaning — remain unintelligible, as in: “...singing the triumphant hymn, shouting, proclaiming and saying...” If we add to this the fact that in many Orthodox churches these prayers, being “secret,” are moreover read behind closed royal doors, and sometimes even behind a drawn altar curtain, then it would be no exaggeration to say that the prayer of thanksgiving has for all practical purposes been dropped from the church service (Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist, Sacrament of the Kingdom, translated from the Russian by Paul Kachur, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, Crestwood, New York 1988, p. 172).

- Fr. Emmanuel Hatzidakis, The Heavenly Banquet, Understanding the Divine Liturgy (hereinafter THB), (Orthodox Witness 20133). In order to simplify this post we have omitted the notes, which can be found in our book. Testimonies by four distinguished authorities, St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop Paul of Finland, Fr. George Mastrantonis and Fr. Alexander Schmemann are appended.

- Bishop Hilarion Alfeyef, “Orthodox Worship as a School of Theology,” Lecture delivered at the Kiev Theological Academy on Sept. 20, 2002.

- Apology I, 67.

- Letter to Xystus, in Eusebius, o.c., p. 291, VII, 9 (PG 20:656).

- VIII.xiii (Ante-Nicene Fathers VII, p. 490).

- Chapter 6 Novella 137 of Justinian, 26 March 565. Quoted by Sove, o.c. The text is rendered here slightly edited. See also Kucharek, o.c., p. 560. Under current practice, the prayers of the Holy Baptism are recited aloud, a fact which points to the reason why the prayers of the Divine Liturgy are not. Whereas in the Divine Liturgy the chanting “covers” the priest during the recitation of the prayers, in the Holy Baptism we do not have any hymns to function in a similar fashion, except for the Katavasiae, in which case they do “cover” a number of prayers.

- Wybrew, o.c., p. 86. Cf. also Patrinacos, o.c., p. 310.

Father, bless!

If I may say so, reading out loud has the added benefit of not allowing any skipping, intentional or not.

And sadly, misunderstanding silent prayers as part of tradition is not surprising. People used to think churches are traditionally painted in very dark tones, after centuries of smoke and grime from the wrong kind of candles covered the original bright colors.

Also sadly and not surprising, this mistaken and spiritually damaging approach to tradition makes Orthodoxy itself look like a dead collection of antiquities, good only for the superstitious and the priests who take advantage of their gullibility. One may argue that those who think of Orthodoxy in this way don’t know any better because they are happy to be ignorant. However, the Holy Scripture places a very serious responsibility on those who cause the stumbling of their lesser brethren.

In my thesis for the Master of Arts degree in Sacred Theology on the subject of the Anaphora of Saint John Chrysostom (1983) I argued for the out loud recitation of the Anaphora and the other prayers of the Divine Liturgy and I have been doing so in my 41 years of priesthood and episcopacy. Some clergy have found it strange and even opposed it; others have supported it and in some cases taken up the practice themselves. When clergy oppose the audible recitation of the prayers they demonstrate their ignorance of the quotes given in this article and of liturgical theology in general. When the faithful hear these prayers most are surprised and pleased. Audibly praying these important orations MUST become the ordinary practice of the Church!